How Did We Get In This Position?

In Part One, Barry Kiefl of Canadian Media Inc. dealt with Canadians' perceptions of CBC Television. Today, how we got there. And Tomorrow, where we go from here.

Back to Barry…

Historical Background

The position the CBC finds itself in today started with the so-called repositioning of CBC in the early 1990’s.

Repositioning is a marketing term used to describe the process that marketers engage in to turn around a failing product or brand. A whole company can be repositioned but this would usually be accomplished not by drastically altering key products but by improving the corporation's image.

Gerard Veilleux, then the president of CBC, led the repositioning of CBC by first announcing at a March 1991 CRTC hearing that English TV would offset the loss of local news programs by regionalizing the news programs on the one station that would be left to serve each province and by creating a network regional news program, Newsmagazine.

The CBC was called to the hearing to explain why CBC TV stations were being closed (they were all eventually reopened). The regional news concept was put together on the eve of the hearing, without thought or planning.

The earlier decision to completely close TV stations was done with such haste that only a last minute intervention by Denis Harvey, VP of English TV at the time, saved the stations in Ottawa and Edmonton.

Of course, this didn’t stop Bob Rabinovitch, who became the president ten years later, from replicating the same mistake, cancelling local TV new programs entirely, including some that were the most watched in their communities and some that were the only local news option. That decision too was reversed before too long.

Harvey heard that a meeting about local stations he was responsible for was taking place in Ottawa without him and he insisted that he be invited.

Newsmagazine was cancelled less than a year later, with dismal ratings. Many of the regional news programs were the third or even fourth rated news program in their markets. This ill-fated concept, which contradicted all scheduling and programming maxims, seemed only to whet the appetite to re-position and re-program English TV.

In January 1992, on the tenth anniversary of The Journal, Mark Starowicz, executive producer, called it "an un-cancellable idea." Less than six months later it was.

The Journal represented the very best of CBC TV. Veilleux and his minions defended the move, pointing to the fact that The Journal was a tired concept. Subject to ever shrinking budgets and resources, yes, but not tired and like a fine Bordeaux, not a product that one just stops producing because it's been around a long time.

That summer of 1991 Veilleux and his staff were laying the groundwork for what was to come; dabbling in research data and organization charts and drafting the paper that Veilleux presented to the CBC Board of Directors in January 1992.

In the six months leading up to this Board meeting he was looking at options such as scheduling The National at 9pm. Veilleux's paper to the Board was a disjointed analysis which listed, among other objectives, that CBC must "demonstrate to Canadians CBC/SRC is an efficiently run corporation with a competent management team."

He called for the creation of a series of six or seven new CBC specialty channels, an idea that he abandoned just a few months later and then just as quickly adopted again in the summer of 1993.

He felt that whatever option was chosen that CBC must "re-think the programming schedule of the main channel." He went on to say that "our news (has) excessive concern for politics" and that there is "real or perceived negativism in our journalism." And, he questioned whether the National/Journal package should be moved to 9pm to take advantage of the "earlier-to-bed tendencies of our audience."

None of these concepts was seriously researched, especially whether people were indeed going to bed earlier. But, if the president said it was true, the staff was prepared to believe him.

Tony Manera, then a vice-president who succeeded Veilleux as president of CBC, admitted to me years afterward that everyone thought there had been proper research. Perhaps members of the Board of Directors felt that they were going to bed earlier than they used to and this was all the research that was necessary.

Veilleux read his Board correctly: the members of the Board were quite prepared to see an earlier news program, especially if it meant that such a program was less "negative" and perhaps more to their liking. At their Board meeting in the spring of 1992 the new TV schedule was approved and the news was moved to 9 o'clock.

Along with this key programming change late night local news was cancelled, the early local news program was lengthened to 90 minutes, to begin at 5:30pm, U.S. programs were all scheduled 7-9pm and 10pm-midnight was turned over to "alternative" programming.

The majority of these decisions didn't make any scheduling sense and weren't backed up by any reasoning. The strategy sounds eerily like the programming concepts recently introduced by CBC TV, with only slight modifications.

This season CBC introduced a 90-minute local news that uses regional stories, followed by a block of foreign programs between 6:30-8pm. Rather than national news at 9 o’clock, it remains at 10 o’clock but The National’s revamped format tends to lighter fare and less in-depth analysis.

Reports say the news-light format was based on advice CBC received from the U.S. news consultant, Frank N. Magid Associates, a company whose style-over-substance journalistic advice was the subject of criticism in journalism schools as long ago as the early 1970’s.

A public relations campaign to influence opinion leaders, especially in Ottawa circles, was launched first by announcing, on May 13, 1992, that The National and The Journal would "move to the heart of prime time...a move designed to enable more Canadians to see the program at what is recognized as the peak viewing hour in Canada."

No mention that the two programs would be replaced by Prime Time News just a few months later. The story hit the front page of most Canadian newspapers and gave the CBC publicity that underscored the dynamic, new leadership of the CBC.

The CBC's new prime time schedule, it was hypothesized, would position the CBC to compete in the "100 channel" TV market of the future. The problem is, of course, that a business doesn't close stores that are doing well because a competitor plans to open up beside some of them.

Prepare for the onslaught of competition, but don't close down profitable ventures until they start losing market share.

Veilleux, his management team and the CBC Board of Directors convinced themselves that they had to abandon their flagship news and current affairs programs to make the English TV service more distinctive. The press were manipulated into believing that it would work, because they assumed that CBC management knew what they were doing.

Unfortunately, this was something more than just a publicity stunt; it goes to the heart of TV: audience habits and tastes. In his forward to the 1992-93 CBC annual report Veilleux referred to the new schedule as "intruding on people's habits," and despite the initial fallout he said the CBC wouldn’t change course.

The press initially bought into the new schedule because Veilleux and the Board were probably right about the need to make CBC more relevant and important to Canadians, but the impetuous means chosen would not have the desired effect.

Audiences to Prime Time News would end up being no larger than The National/Journal hour, even though there were more people available to watch TV at 9pm. The decline of the longer, earlier, regionalized 5:30 news programs was quick.

CTV and other competitor’s news programs benefited from these various changes and touted how they were better positioned for a more competitive marketplace. John Cassady, then president of CTV, upon first hearing of the 9pm decision, compared the move to Coke's disastrous decision to change its taste formula. Veilleux's ill-advised repositioning cost the CBC dearly. By 1994 The National had returned to its customary 10 o’clock time slot.

CBC in 2010

So where is the CBC 20 years later; doomed to repeat the ten year cycle of past presidents? Well, for one, the 100 channel universe has come and gone and has been replaced by an infinite number of channels. CBC managed to open one important specialty channel, CBC News Network in 1989.

It used to be called Newsworld but, according to Hubert Lacroix, the current president of CBC, “tons of data” supported changing the name, as well as the format of The National. CBC also operates a couple of smaller specialty channels that few Canadians know about, let alone watch.

And, CBC also has a presence on the internet, cbc.ca, but the audience share of most web sites, other the Google’s or Microsoft’s, is infinitesimal, including CBC’s. cbc.ca’s national average audience would be less than the smallest CBC TV or radio station in the country and its audience share needs 3 decimal points to calculate.

Tellingly, all these years later it is the main CBC TV channel and CBC radio that are vital in audience terms but the data from our TV/ Radio Trends survey reveal the main TV channel has been drifting downward in the past decade. Viewer satisfaction and support for the main channel has been waning.

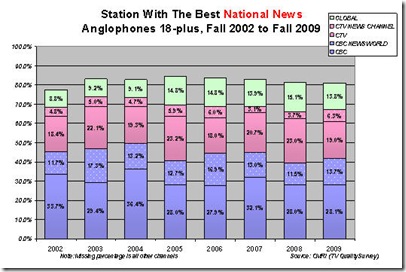

Yet, despite this erosion, CBC TV is still considered by Canadians as having the best national TV news. All that tinkering in the 1990’s didn’t affect the important role that CBC national news plays. Hopefully, the CBC news department takes another look at the tons of data that led to recent changes and doesn’t lose its historic place.

The chart above shows that for eight years running CBC TV/Newsworld have had a clear lead over CTV/Newsnet and Global TV, both of whom invest heavily in national news programs.

When it comes to international news, CBC TV/Newsworld is the only Canadian option that can compete with CNN/Headline News. CTV and Global are not viable options as far as Canadians are concerned (Global is so insignificant the results cannot be displayed in the chart).

CNN is the leader in international news but CBC and its sister network share the international news stage with the American news network and maintain a Canadian perspective on the rest of the world.

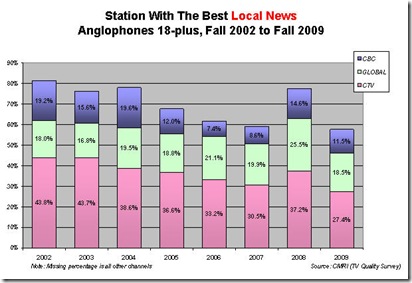

However, the two Canadian private networks over the past decade have collectively maintained a stranglehold in local news. CTV and Global combined have for most of the past decade had roughly four times the number of viewers who chose them as the best for local news coverage.

In the chart below CBC TV began the decade slightly ahead of Global but by mid-decade had become a distant third choice and has remained there in the ensuing years.

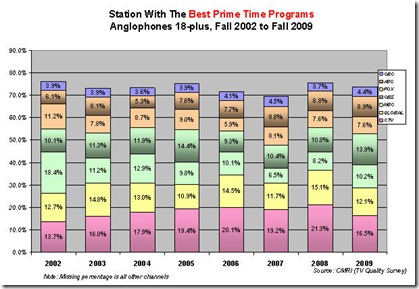

Unfortunately, another constant and unchanging perception about CBC TV is that it does not have the best prime time offerings.

Fewer than 5% of respondents in our annual survey for eight consecutive years have chosen CBC TV as having the best prime time programs, which even the CBC says is the most important part of the schedule.

The latest effort at a 90-minute local news program, another version of a block of U.S. and other foreign programs 6:30-8pm and a mélange of mostly unremarkable Canadian comedy and drama 8-10pm, have had no effect on public perception. Most networks with this kind of prime time record would have been shut down long ago.

Tomorrow: "To Infinity and Beyond!"

1 comment:

Given everything the temptation must be to operate the main TV channel as a kind of Potemkin operation: it's there, it seems nice enough while channel-changers are drifting through, but there's nothing really happening or being made. That would harvest a lot of the goodwill (and money dependent on it) at next to no money, and of course some would say it has already happened.

Post a Comment